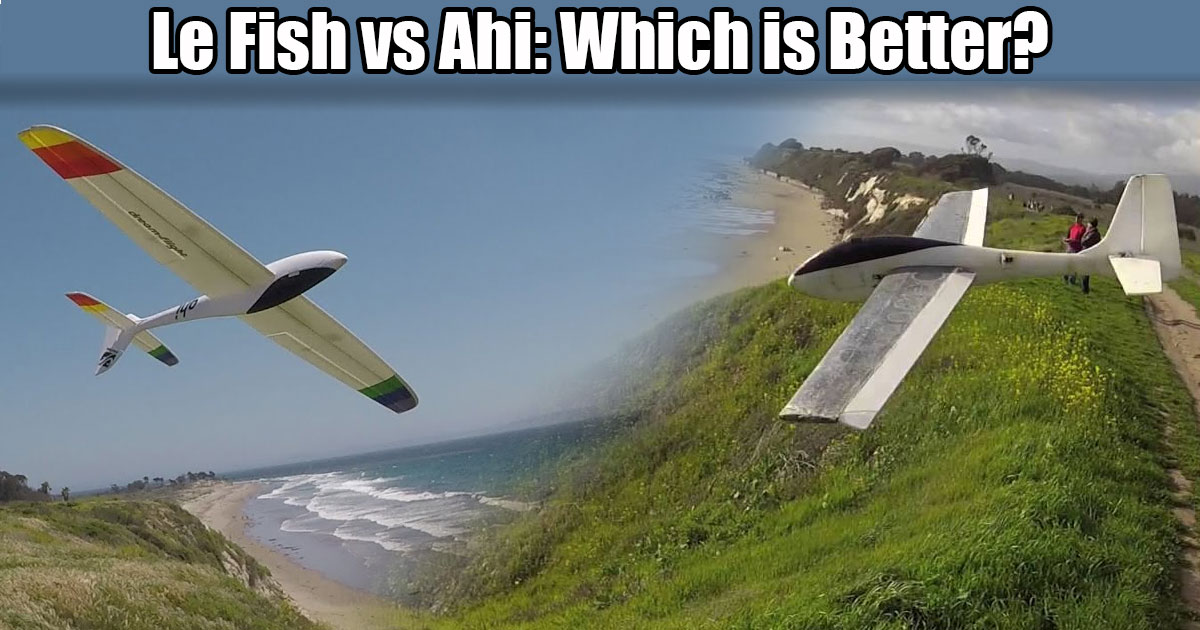

Le Fish vs Ahi: Which is Better?

You’ve flown both, what’s your feeling?

Great question and one I’ve obviously given a lot of thought to, being the designer of Le Fish, as well as a huge fan of the Ahi!

They’re different planes, that’s for sure. The Ahi, being smaller and less draggy thanks to a combination of its sophisticated design and molded construction, tends to feel like the faster and more agile plane in many situations. Its roll rate is higher, and it has that uniquely Dream Flight trait of being able to “weasel” out of tight situations that would represent an unavoidable crash with most other gliders. It can fly extremely precisely in a small space, like a miniature precision slope aerobat, but it can also let loose with a beautiful flat spin, and is quite amenable to being hucked around with joyful abandon by your typical slope pilot. It’s an absolutely fantastic design and has enjoyed well-deserved popularity amongst both aerobatics aficionados as well as sport flyers the world over. I am so happy and grateful that it exists and have written and said the same many times both online and in person.

Beyond its performance, however, the huge advantage of the Ahi over all other aerobatics gliders in the marketplace is its accessibility and repeatability. Thanks to its high quality molded construction, every Ahi you build will fly just like the last one, and it won’t take long to put a new one together or swap in a spare part if something gets broken or worn out. It won’t cost too much, either, at least not compared to a composite aerobatics glider. You don’t need a lot of hobby or model experience, nor a big time commitment, to have a great flying Ahi. Just assemble it following the very clear and well-illustrated instructions, and you’ll have an awesome little plane, virtually guaranteed to provide outstanding and very fun performance. It’s pretty hard to screw one up if you build it stock and use Dream-Flight components!

Beyond that, the Ahi was designed by someone – Michael Richter – with an actual aeronautics background, including an academic degree as well as professional experience building 1:1 scale sailplanes with Schempp-Hirth in Germany. Michael has told me how he built multiple Ahi prototypes, testing all sorts of variables including airfoil, empennage sizes, and so forth, over the course of a good deal of time – months if not years – until he was satisfied with the design’s performance. He’s a meticulous builder and very talented pilot, and is always cognizant that he’s creating a plane not just for his own satisfaction, but also one that will ultimately have to live up to the expectations and demands of the worldwide slope soaring community.

By necessity, his designs need to appeal to a broad audience, and provide satisfying performance across the widest range of slope sites and flying styles possible. They have to be affordable products for a global market, something that he can supply in quantity and economically to distributors around the world. He has to seriously commit to whatever prototype he finally decides on, investing significant, non-trivial sums of his own money into creating expensive injection molds and seeing through all the myriad details involved in getting an aircraft from concept to reality. You can bet he’s really put in the work to make sure it’s the best plane he can come up with, and it absolutely shows in the end product. The Ahi is a fantastic little plane, but it didn’t get that way by accident. Dream Flight products are on a truly different level than anything else in slope soaring world, and are some of the best RC hobby products I’ve ever purchased – bar none.

By way of comparison, the Le Fish was drawn in a notebook by someone – me, Steve Lange – who was really enthusiastic about aerobatics gliders and developing his aerobatic flying skills, and had scratchbuilt a number of EPP planes, but had no formal training in aeronautics to speak of. Much of what I knew of model airplane design theory I’d learned from Michael Richter, or from texts and resources he suggested I study. I’d also spent a good deal of time with Babelfish translating French web pages dedicated to aerobatics gliders and flying. The Le Fish borrowed quite liberally from a variety of preceding glider designs, primarily the open source Mini-Toons as well as the Aeromod Voltij, and combined their fish-like fuselage shapes with the straight leading edge wing planform as seen on the fullscale Fox and Swift aerobatics gliders as well as the Edge 540 aerobatics plane. My desire was basically to have something like a Weasel – with its light lift capability, its agility and its durability – enhanced with a rudder and near-perfect inverted flight.

I’d bought and built a Gerasis 2.2m MDM-1 Fox scale glider as well as an Aeromod Voltij, which was my first dedicated composite aerobat, but they were too heavy to fly well in Ellwood’s typically light conditions, and they weren’t really anywhere near as durable as a Weasel – meaning they weren’t really suitable for the “in your face” style of low altitude sport flying that’s always been popular at Ellwood and other coastal sites in California. Creating an EPP aerobatics glider was an obvious solution, except nothing matching that description existed in the US at the time, and there were precious few options available worldwide – the best-known (using that term loosely) being the Mini-Toons, an open source design from France. I’d tried to get one of those, but at the time the French were using different cutting software than the foam cutters in the US, so despite the fact the design was free to download via the EPP-Concept website, I just couldn’t find a way to get one produced locally. Likewise, I found the shipping from France to be cost-prohibitive for a foamie, and I’d been doing a lot of EPP scratchbuilding anyways, and had some of my own ideas I wanted to try out… you can see where this road is leading.

So, Le Fish was literally just a sketch of something that I thought looked cool and hoped would work out OK. I made the original drawing and then reverse engineered the dimensions by measuring each feature of the sketch using the pre-decided 1.5m wingspan as a scale reference. I didn’t really calculate areas or moment or anything like that, it was very much a TLAR – “That Looks About Right” – exercise, heavily informed by the previously-mentioned designs, my own sense of what seemed visually correct, and experience scratchbuilding other designs. I figured it made sense to at least work from some well-proven ideas – like the SB96V/SB96VS airfoil combination that many of the French aerobatics planes used, and the then-popular (in the US, anyways) EPP construction techniques of using thinned Goop, strapping tape, Solartex and Ultracote to finish the plane.

These drawings and my thoughts about the design were sent over to Jack Cooper at Leading Edge Gliders (LEG) who promptly cut out parts from my drawings on the understanding that, should the prototype prove successful, the design could be turned into a LEG product. The resulting plane absolutely impressed me and vastly exceeded my expectations for something that I’d both designed and built. I had an absolute blast flying it, and it was totally unlike anything I’d flown previously… very agile for a 1.5m plane, very good inverted/outside performance, great knife edge, powerful rudder, much faster than expected by the tall fuse and thick wings, very durable, and very, very fun. Compared to everything else I’d flown up to that point in early 2006, it was an absolute winner and even better than I had dared to hope for while designing it.

With that said, as much as Le Fish was a fun glider and went on to be one of LEG’s best-selling planes for many years to follow, the original prototype didn’t quite achieve my original goal of creating an aerobat that could fly in lift similar to a Weasel. The prototype had been built more like a typical Power Scale Soaring (PSS) or Dynamic Soaring (DS) plane from the same era, and its All Up Weight (AUW) of 38oz reflected this. It just didn’t perform all that great in light lift, though it was a ton of fun in stronger lift. It wasn’t until 2011, when a Swiss friend named Peter Richner began building the Le Fish to unheard-of, sub 20oz AUWs through a then-radical combination of Depron flying surfaces, “Swissed” lightening holes, thin laminating film covering, and minimal carbon reinforcement, that the original vision for Le Fish as a light lift aerobat was realized. (This thread documents that process, along with the Madstab experimentations that followed shortly thereafter)

So without belaboring the history any further, it should be more than obvious that the Le Fish as such is a design that’s been undergoing constant evolution since the beginning. For his part, Jack has been making adjustments to the kits over the years, incorporating both his own ideas and responses to customer feedback. Other builders and kitters, using the open source original drawing and subsequent Creative Commons plan, have created their own variations of the design, often incorporating new and novel construction ideas. Testing, experimentation, adaptation and collaboration have exemplified the Le Fish project over its 13 year history.

So, when we get down to brass tacks – to the question of which plane flies better, the Le Fish or the Ahi – I think the question has to be “which Le Fish?”, because not all Le Fish are created equal, and that’s by design, if you’ll pardon the pun. My own ultralight Le Fish itself underwent a number of evolutions between 2011 and 2013, as I continued to try different ideas out, and the plane flew much better for me in 2013 than it did in 2011. My flying style had adapted to it, as well. The Le Fish is really more like an open source software project than it is like a consumer product, and it can reward the experienced tinkerer with a plane that will be uniquely suited to the pilot’s specific preferences and flying locales, be that DS aerobatics at 100mph+ like Alex Hewson from New Zealand, or flipping around and railsliding handrailings in light coastal lift, like in my videos from Long Beach. It may be that we’ll see similar from the Ahi in time, but to date, I haven’t seen quite as much modding or customization on the airframe as I have with Le Fish.

A madstab-equipped ultralight Le Fish in decent lift at Ellwood is a pretty magnificent thing, offering a unique combination of speed (not too fast, not too slow), presence, agility and aerobatic capability that, at my coastal spots, is pretty special. Which should come as no surprise, since the plane’s features were iterated on repeatedly with an eye towards improving its performance in that specific setting: steady, mostly vertical lift at relatively modest windspeeds, flying in a small aerobatics box, almost exclusively at low altitude.

While the Ahi also excels in such conditions, there are salient differences between the planes. Whether these differences mean one design is better or worse than the other is really going to come down to pilot preference; they are both extremely capable, and there is a good deal of overlap, but each design has attributes that make it excel in an area where the other is weak, and vice versa. (Note: For the discussion that follows, please understand that I’m comparing an ultralight ~17oz Le Fish with madstab to a box-stock Ahi in typical 8-12mph lift at Ellwoood Mesa, a small coastal cliff, unless otherwise noted.)

One of the most obvious examples of difference is the Ahi’s inverted performance, which gives up a lot in comparison to Le Fish; even with snapflaps and 4 axis to help, it loses a lot more energy when performing outside figures, and many pilots – even very experienced ones – have expressed difficulty in getting reliable outside loops in non-coastal / cliff conditions. Modding the Ahi to use fullspan flaperons could certainly help, but the Libelle’s airfoil – which the Ahi shares – is more optimized for upright flight than the purpose-designed SB96V and SB96VS combination, which are _the_ reference aerobatics airfoils for very good reason, so you’re always going to be fighting something intrinsic to the Ahi’s design, when it comes to inverted performance.

Now, in fairness, this airfoil also gives the Ahi some wonderful versatility in a wide variety of different flying sites and lift conditions, and helps imbue it with the quick, energetic upright flight characteristic that so typifies what the plane is all about. That little bit of extra zing and energy helps the Ahi maintain speed through situations that would likely see the Le Fish bog down and crash, meaning I’m able to get away with some things with an Ahi that I just can’t with a Le Fish. It also means that there is a distinct difference when flying the Ahi inverted versus upright, and this carries over into the snap and spin figures looking and feeling distinctly different when they’re performed upright/positive versus inverted/negative. That means that, with the Ahi, although your inverted performance isn’t as good overall, you’re essentially getting double the number of unique-looking aerobatics figures, as compared to a plane like the Voltij, or to a lesser degree the Le Fish, which basically does all the figures the same regardless of whether they’re upright or inverted. (Note: conventional wisdom holds that a “fully aerobatic” plane should be able to do all figures with equal facility both upright and inverted; it’s sort of my opinion that a small difference between the two is kind of cool, but this isn’t generally a common position as far as I know).

The airfoil, combined with a comparatively small empennage and fuselage relative to most other aerobatics designs, makes the Ahi probably one of the lowest drag aerobats on the market. It is, to borrow a French phrase, extremely “polyvalent,” meaning it’s versatile and capable of adapting to a very broad range of conditions and flying sites. I’ve flown mine unballasted in 35mph+ wind in the Pyrenees, something that would have been impossible with a 17oz ultralight Le Fish. The Ahi has also proven to be an extremely capable little thermal machine, able to exploit often challenging Alpine lift in a manner far outstripping its modest 1.2m wingspan and aerobatic orientation (it’s still easily outperformed by 2m+ composite gliders in tricky mountain thermal conditions, but that’s hardly a disparaging comparison for 400gm EPO aerobatics glider). This is one area of the analysis where there’s really no contest; although the ultralight Le Fish has demonstrated very good performance from sea level to 10,000ft, the Ahi has an even broader capability envelope.

One area where there’s another really clear distinction between the planes is in durability, especially as regards VTPR flying in general, and inverted fin drags in specific. Now, granted, this is an area that may be a little outside the realm of the “average sport pilot,” but since this article deals with my impressions of the differences between the planes, and this difference is actually highly relevant to my flying, I’m feeling like it’s important to mention it.

The Ahi’s rudder features a prominent counterbalance on the upper ⅓ or so of the surface. This counterbalance helps to increase the rudder efficacy while allowing it to remain shorter in height (and hence creating less drag) than many other aerobatic designs. However, for VTPR flying, it has the significant disadvantage of creating an unavoidable weak point, insofar as one of the core “moves” of VTPR is to touch the top of the rudder against the ground (or grass, etc.) while flying inverted. To date I have torn the rudder off of every single Ahi that I’ve flown any amount of VTPR with. I have begun modding the rudder during assembly by cutting it loose from the rudder post and re-hinging it with CA hinges, as this is the only way to keep the rudder attached to the plane for more than a couple flights (for me). Almost all other VTPR-oriented gliders feature vertical stabilizers where the non-moving parts are extended above and below the rudder, and the rudder itself sweeping away from these contact points, so that the fixed portions will be contacting the ground during upright and inverted drags rather than the rudder. It’s not an accident that the gliders are designed this way, as this kind of flying is intrinsic to VTPR. It’s a subtle detail, but experience with the Ahi demonstrates that it exists for a very good reason.

The tail in general is a weak point on the Ahi, especially the small fixed portion underneath the horizontal stabilizer, which will almost inevitably crack underneath the leading edge of that surface after a few flights (surely also related to my proclivity for inverted fin drags). This can have a significant negative affect on the stability of the horizontal stabilizer, as once this section of the fuselage gets cracked, the entire stab will begin rotating in the vertical / yaw axis when elevator deflections are applied, due to the reduction in stability caused by this weak point. It is also a leading cause of the horizontal stabilizer itself getting out of square relative to the wing. It winds up needing a lot of maintenance, though a decent longterm fix is to embed a small piece of carbon fiber reinforcement, to help shore up this small fixed portion of the stab to the tailboom ahead of it, thereby preventing it from breaking repeatedly.

There are a few other more minor durability-related gripes, like how the tiny screws that are meant to secure the wing joiner tube do a poor job of actually securing the wing, so you’re constantly having to reset the wings after a firm landing or crash. Because of the tiny heads of the screws used for this purpose, you’ll almost inevitably strip them before too long, leading to them needing to be replaced or just removed altogether. It’s a minor annoyance compared to the tail surfaces, but an annoyance nonetheless. With that said, it is quite nice to be able to remove the wings for travel and storage, and any multipiece wing is going to have some hassles compared to a 1 piece plane, so that’s just sort of the facts of life. It still feels like this system could be improved, however.

Lastly, the magnets used in the Ahi, while being a nice idea, have proven to be mostly ineffective. The ones in the wing root are undersized and aligned at an angle to the forces they face, meaning they’re less effective than they could be were they aligned in the vertical plane,and they do nothing to help avoid the issue with the joiner tube screws mentioned above. The magnets in the canopy have proven totally ineffective at retaining the canopy, to the extent that I have to fly with strips of electrical tape on either side of the cockpit to keep the canopy from being ejected. (Outside snaprolls are particularly good at launching the canopy, in case you’re interested).

Obviously, an EPO airplane flown frequently, especially one that’s flown in a VTPR style, is going to have a potentially hard life, and it’s generally not going to hold up as well over time as an EPP plane. Furthermore, an EPP plane can be repaired and recovered to a like-new condition after a few seasons’ flying, whereas an EPO plane will likely need parts or the entire airframe replaced. EPO, of course, comes with a number of advantages, many of which we’ve already touched on and which are for the most part pretty well understood: fast and easy build, great surface finish, lightweight, easy to get repeatable results from, easy to repair with a variety of adhesives, etc. How often repairs happen will vary significantly depending on the pilot and his/her ability and preferences, but overall, I’ve found that our Ahis have needed quite a lot of maintenance compared to the EPP aerobatics planes we own.

Another big difference between the planes is the build. With the Ahi, it’s basically around 90-120 minutes of assembly, whereas with the Le Fish it’s going to be an actual build, and it will be significantly longer – probably by an order of magnitude. Because the Ahi is so straightforward and well designed, and supported with great instructions, it’s very easy to get a good result, even for someone who has never built a model plane before. The Le Fish generally comes with no instructions whatsoever, and the builder is mostly left to their own devices to figure it all out, including specific adaptations/mods/etc to best suit their local flying site and style. Granted, the Le Fish and its larger 1.5m wingspan is probably a bit more tolerant of builder modifications and experimentations than the Ahi, which in my experience has proven to be so highly optimized that mods have as good a chance of degrading as improving the performance of the plane as a whole.

The net/net of this comparison is that the Ahi is just much easier and accessible for the average builder and pilot, mainly because there’s no build to speak of, just a brief and largely enjoyable assembly. But the Le Fish is likely more amenable to customization during the build process – assuming the builder is up to the task, and the mods are well-selected and likely to improve the performance for the desired flying site / style / etc. This last claim is obviously debatable, and in fairness I’ve mostly kept my Ahis stock so that I can give honest and direct opinions of the design “as delivered.” So it’s quite possible that I’m poorly informed as regards Ahi mods, and/or just had bad luck or poor implementation on the ones I’ve tried.

Moving on, in terms of unique tricks, or gimmicks, the Le Fish with madstab obviously has the flip, and the Ahi has the flatspin. I haven’t tried flatspinning the Le Fish yet, and I’ve had awful luck getting a madstab to work on the Ahi without ruining the things that make an Ahi fun (the “mods degrading performance” thing I mentioned previously), so for the time being, I’m operating from the position that it’s going to be pilot preference which of these tricks you think is more fun or cool. Despite looking neat in the air and usually impressing spectators who don’t know better, neither of these gimmicks takes any particular skill to execute; you simply move the stick(s) to a certain position and then the trick happens, and it stops when you release the stick(s). This is why I refer to them as tricks or gimmicks. Each trick has its proponents and detractors, though for my part, I love them both and honestly can’t understand people who don’t enjoy them, but that’s just me. In a perfect world, it’s my opinion that you want to have a plane that can do both (along with the full complement of normal aerobatic figures, etc), but so far I’ve only seen that with Francois Cahour’s gliders, and they represent a level of complexity that goes well beyond the scope of this discussion.

So, I’ve catalogued a number of observations about each plane, and I hope I’ve made it clear that, for me, both planes have their positives and negatives. Compared to an ultralight Le Fish, the Ahi is going to be the more versatile and adaptable plane for the wider variety of slope sites, there’s no question. It flies fast, energetically, it has a great roll rate, and it looks cool and is widely available. These are all things that traditionally define a successful and popular slope plane, and I strongly believe the Ahi and Michael deserve all the accolades they’re getting. It’s a fantastic plane and for my part, I’ve certainly tried to demonstrate what it’s capable of – completely stock – to the best of my ability.

Now, the Le Fish can – and has – been adapted by its builders to suit many different slope sites around the world, and has proven extremely versatile in its own right. Compared to the Ahi, it has superior inverted performance and durability – without question. It is highly amenable to being modded and customized, and has a free-as-in-beer plan available for anyone to download and use for their own purposes. It’s been a fantastic plane and for my part, I’ve also tried to the best of my ability to demonstrate what it’s capable of, in its various forms over the years.

With that said, for me, Steve Lange, guy who flies VTPR at Ellwood and France and likes to drag his rudder through the grass – well, for me, asking me to choose between these two airframes is like asking a painter whether he likes his broad brush or his detail brush better. It’s sort of a silly question. I like having both, plus all the other brushes and paints I can stash in my artist box. Each one does something a little different from the rest, and those differences are what make them interesting. I’m solidly in the “both/and” column as opposed to the “either/or”… more aerobatics gliders is always the right answer.